Here, I’ll be posting a daily something about this year’s online LFF. It may be a summary of the films I’ve watched and the thoughts I’ve had, or it may be an in-depth review of something that struck a chord. Or maybe even both.

Day 13 – October 17th

Ammonite (2020) dir. Francis Lee

Francis Lee’s period romantic drama, inspired by the real life of the fossil hunter Mary Anning closed this year’s London Film Festival in cinemas across the country. As such, it was the only film from the programme that I got to experience on a big screen.

The windswept Lyme Regis coastline is rendered onscreen with painterly precision whilst the lashing of the waves reverberated around the auditorium in immersive fashion. The quieter moments were slightly undercut by the whistling of the fizzy drink carbonators in the room next door, but no matter.

As for the film itself, it’s easy to compare this love story between the brusque Mary Anning and the frail, bereaved Charlotte Murchison who ends up in her care to Portrait of a Lady on Fire – the period detail, the same-sex attraction, the position of women in a man’s world. And yet, as strong as this is it does lack some of the thematic heft of Celine Sciamma’s film.

That said though, it’s still just as romantic a film. The way that Mary and Charlotte’s attraction builds from chaste looks and brief hand holding to the most extraordinary passion is well paced, helped by Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan’s nuanced chemistry.

It’s also a lot earthier and grimier than Portrait, Lee juxtaposes this age of scientific discovery and wonder with the mud and toil of fossil hunting. Anning and Murchison are also disparate in their social standing, an undercurrent running through the film that never quite builds to something substantial.

Lovers Rock (2020) dir. Steve McQueen

Steve McQueen’s second film from his Small Axe series is much looser on plot than Mangrove but no less powerful, albeit for different reasons.

The plot, slight though it is, revolves around Martha (An assured, captivating debut perfomance by Amarah-Jae St Aubyn) a young woman from what we can quickly surmise is a strict religious background as she attends a house party in west London. There she dances, drinks, loses her friend Patty and gains the romantic attentions of Franklyn, ably batting off the more sinister advances of Bammy. And aside from a credulity-stretchingly coincidental appearance by a resentful family friend, that’s it.

McQueen moves around the party from room to room the queue for the toilets, the smoking area outside. His camera weaves between the revellers on the dancefloor, focusing on entwined bodies, embracing couples and the sweat dripping down the wallpaper. It’s a stripped back, almost completely non-narrative film that euphorically evokes universal themes of youth and love as well as representing West Indian culture and music in a way that we rarely see. It’s disappointing not to have seen this on a big screen with a proper sound system. Imagining how Foolish Game and the film’s final, delirious, chest-pounding sweat-soaked climax would play to a cinema just gives me chills.

Day 12 – October 16th

Nomadland (2020) dir. Chloé Zhao

Chinese director Chloé Zhao is currently at work on The Eternals, the latest in a long line of massive Marvel blockbusters. That gig will hopefully ensure that she can continue to make these smaller-scale, immersive character pieces. Failing that, a well-deserved Best Director Oscar at next year’s awards ceremony should surely cement her credentials.

Nomadland is a masterpiece. A meditative road movie that never meanders as it travels across the contemporary American West. Frances McDormand plays Fern, a widow who has embarked on a nomadic existence following the death of her husband and the disbandment of her whole community following the closure of the local sheetrock business.

Zhao’s signature style is to use actors who play fictionalised versions of themselves – imagine the results if she applies that to a superhero movie! – and as a result, Oscar winning actress Frances McDormand becomes fully immersed in this transitory existence.

This is a beautiful film, both spiritually and visually. The sense of community between the modern-day nomads called to mind the humane spirit of Debra Granik’s Leave No Trace. Joshua James Richards’ stunningly renders this picturesque wilderness whilst also highlighting the hidden dangers of being out there alone.

This is, without question, the finest film of both the festival and the year. A deeply moving portrayal of the human spirit, economic collapse and community displacement that, given the direction current events are headed, will continue to be timely for a long time to come.

Day 11 – October 15th

Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and Legendary Tapes (2020) dir. Caroline Catz

Delia Derbyshire created the theme tune to Doctor Who. Ron Grainer may have written it but it’s the otherworldly magic that Derbyshire brought to Grainer’s composition that ensured the longevity and one or two pale imitations.

Due to the way BBC contracts worked at the time, Delia Derbyshire never really got the recognition she deserved for her work, financial or otherwise. It was a similar story for Raymond Cusack, who so iconically designed the Daleks. Neither of them got a share of the lucrative royalties both creations have chalked up over the years. Both were given passing nods in Mark Gatiss’ tremendous drama An Adventure in Space and Time but ultimately that undersold their work just as much as their contemporaries did.

The Myths and Legendary Tapes goes some way to cementing Derbyshire’s legacy beyond just that theme tune. Caroline Catz’s film is a mixture of documentary, biopic and sonic experiment (the score is a collaboration across time between Derbyshire and Cosey Fanni Tutti). As such, it avoids many of the pitfalls of many cradle to grave biopics.

Deftly weaving talking heads (including fellow Radiophonic Workshop legend Brian Hodgson) with acted reconstructions of moments from her career and Cosey Fanni Tutti’s connecting of sonic pathways, Catz presents a rich and textured portrait of a pioneer.

The real strength of the film is how it reclaims Derbyshire’s story for herself. She died in 2001 and a lot of obituaries and a radio play focused on her as a sad alcoholic who never got her due. Catz doesn’t shy away from Derbyshire’s Guinness and snuff habits but instead presents them as character flaws rather than the full story.

Delia was far more interesting than what she put up her nose or down her throat. She was a mathematician and electronic musician who wanted to create sounds that had never been heard before. She achieved that time and again, and, at last, that work is properly celebrated. Aptly enough it’s in an experimental film which may test some people’s patience but is ultimately a richly rewarding experience.

Day 10 – October 14th

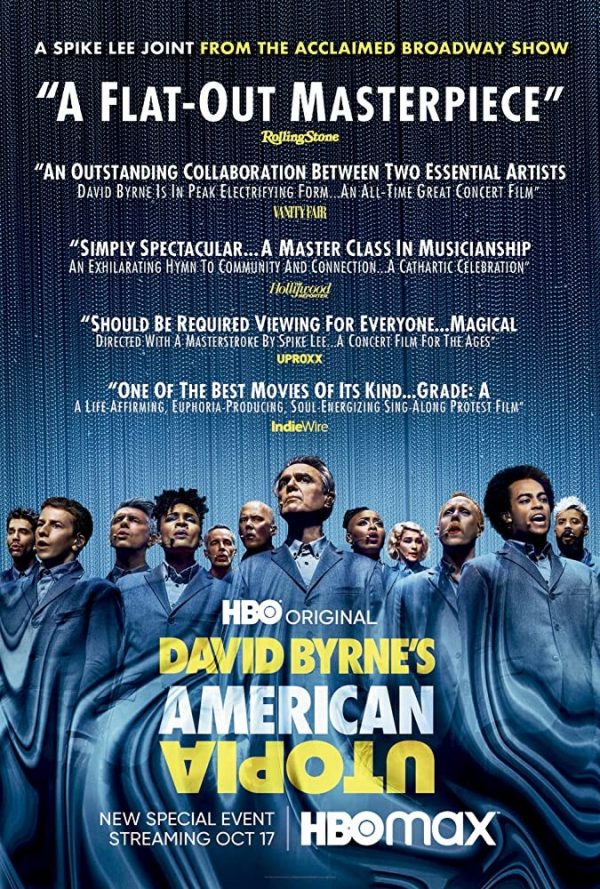

David Byrne’s American Utopia (2020) dir. Spike Lee

Earlier this year, I wrote at length about Nick Cave’s solo concert film Idiot Prayer: Nick Cave Alone at Alexandra Palace. That film was a haunting career retrospective that, in the midst of the pandemic, felt like a beautiful celebration of our dormant arts venues as much as it did Cave’s diverse range of work.

David Byrne’s American Utopia is also a retrospective, one that takes us from Byrne’s time in Talking Heads through to his most recent solo album American Utopia via a barnstorming cover of Janelle Monae’s Hell You Talmabout. It also works as a retrospective of America itself, beginning with Byrne talking about how open and active our brains are at birth, before tracing a country from its aspirational ideals (songs like Don’t Worry About the Government) through poor voter engagement (Blind) to where it’s going next (One Fine Day, Road to Nowhere).

And finally, through Lee’s frenetic direction and Ellen Kuras’ swooping cinematography the film feels like a retrospective of the sheer life affirming joy of witnessing live performance. We feel like we’re on, around and above the stage as Byrne and his (untethered) band move around the space in beautifully choreographed numbers.

With a looming US presidential election it feels like we’re further away from an American Utopia than ever. Spike Lee’s addition of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd at the close of the Hell You Talmbout sequence powerfully emphasises that. Similarly, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic continues to ensure that we’re unlikely to see live performance on this scale any time soon. And yet, there’s something joyous and hopeful about American Utopia – it’s not a lament for what we’ve lost, but a celebration of what we’ll have again, somewhere further down the road to nowhere.

Limbo (2020) dir. Ben Sharrock

This wry comedy about a group of asylum seekers awaiting settled status on a Hebridean island was one of my most anticipated films of the festival. That it didn’t quite live up to expectations is possibly more my fault than it is the fault of the film itself.

On the one hand, it has this absurdist strain of humour running through it, exemplified by the opening sequence of a cultural integration class about consent set to Hot Chocolate’s It Started With a Kiss, performed by a gloriously off-kilter Sidse Babett Knudsen. The local Hebridean community that bemusedly try to welcome their new residents is similarly hilarious and Scottish comedy stalwarts Sanjeev Kohli (playing a shopkeeper, just once I wish Sanjeev would be cast as a customer) and Raymond Mearns delivering laugh out loud cameos.

There’s a good balance of these lighter elements with the theme of cultural identity. Western culture looms large as our central character Omar and his housemates (including the scene stealing Vikash Bhai as Freddie Mercury obsessed Farhad) watch Friends whilst discussing Tom Cruise and Chelsea football club. Omar’s oud is the central metaphor for the risk of cultural erasure, as a hand injury incurred during his escape from his native Syria threatens his ability to play the instrument ever again. Without it, who is he? It’s a quietly powerful conceit, and Amir El-Masry plays Omar stoically with a subtle anguish coming more and more to the fore as the film continues.

My main issue is the uneven tone as writer/director Sharrock struggles to manage the transition from melancholy with a tinge of absurdist comedy to harrowing tragedy. Without spoiling it too much, Omar makes a discovery which feels like a contrived attempt to hammer home the drama in a film in which far more banal everyday events are the most interesting elements.

After Love (2020) dir. Aleem Khan

When Mary’s husband Ahmed drops dead suddenly, and unexpectedly she finds her life upended further by a phonecall from the mysterious “G” which reveals that Ahmed was living a secret life in Calais.

First thing’s first – Joanna Scanlan is excellent in this, the way that Mary ingratiates her way into G’s life without indicating who she really is, is entirely predictable and not particularly plausible plotwise. However, it’s sold entirely by Scanlan’s affecting performance of tentative silence, as if the shock of Ahmed’s death has rendered her almost mute.

Structurally, the film plays out in a way similar to the Kubler-Ross five stages of grief as more information about Ahmed’s life is revealed, Mary moves towards eventual acceptance, maybe even forgiveness.

It’s a three hander of strong performances, which tests credulity at times and skirts around more interesting themes – Ahmed was staunchly religious at home in Dover, but drank beer in Calais whilst Mary, a convert to Islam, still maintains a distance from some of those traditions.

It’s a flawed debut, but Khan shows promise in his visual and aural sense. There are lots of wide shots to emphasise Mary’s loneliness and Ahmed’s absence whilst the ringing of her husband’s phone starts to act like the Telltale Heart as the film plays out. Having also recently seen his short film Three Brothers, Khan is marking himself out as a director of complex family dramas and I’m keen to see what he does next.

Day 9 – October 13th

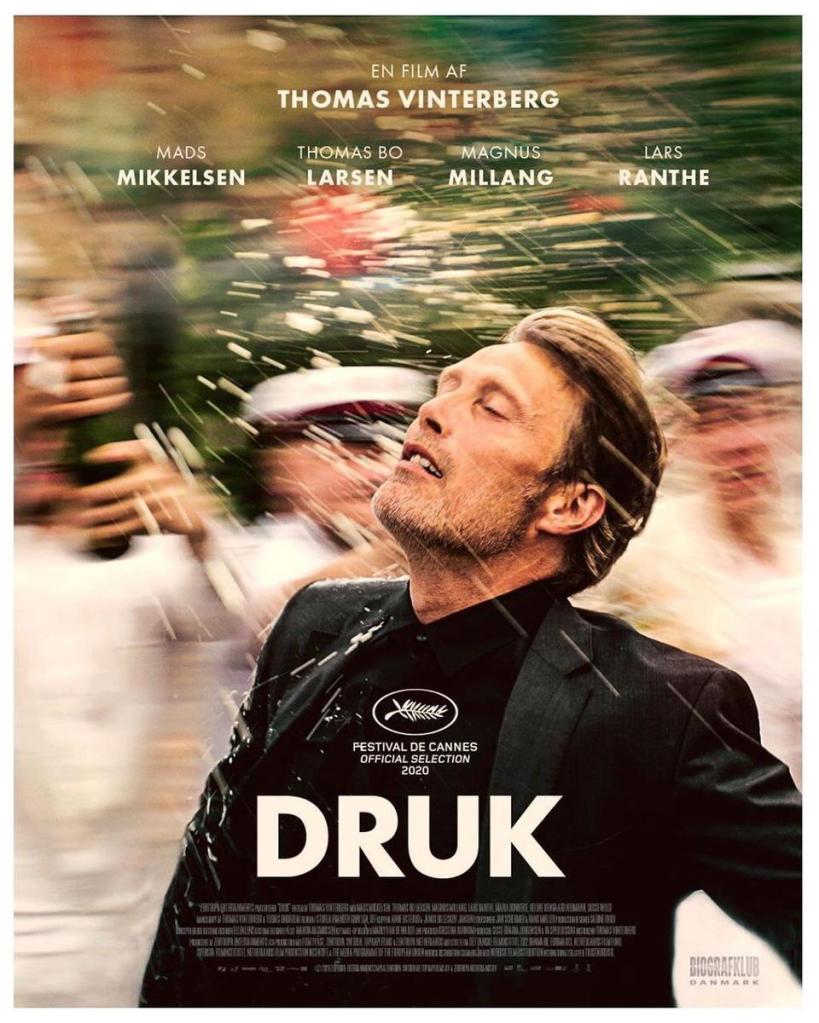

Another Round (2020) dir. Thomas Vinterberg

There’s a long list of films about male middle-aged angst and a similarly long list of films about alcohol abuse. Thomas Vinterberg’s latest Another Round (or Druk, to give it the domestic title) is a fairly throwaway entry in either pantheon but an incredibly entertaining one nonetheless.

Martin (Mads Mikkelsen) is a high school history teacher who’s staring down the barrel of middle age. His wife and kids ignore him, and he lifelessly rattles off the core curriculum to his alarmed pupils. During a 40th birthday celebration for friend and colleague Nikolaj, he hears of a theory by the Norwegian psychiatrist Finn Skarderud – that human beings are born with a blood alcohol deficiency of 0.05%, and that we’d be a lot happier and healthier if we could maintain such a level. The next day Martin sneaks a few swigs of vodka before class. Soon enough, he and his friends set out to prove Skarderud’s philosophy and Martin in particular finds that he’s becoming a better teacher, husband and father as a result.

Inevitably of course, they take things too far and it’s at the “ignition point” (where you either give up and go home or push through and carry on drinking) that the film begins to stagger along and slur its message. There are some glaring tonal inconsistencies towards the end, as Vinterberg becomes more keen on exploring the dangers of Danish drinking culture than testing Skarderund’s hypothesis in any real detail.

The other issue is the female characters in the film, all of which are fairly unsympathetic nags that are dragging their husbands down. It doesn’t sit right, and calls to mind a lot of the laddish comedies – The Hangover, Hall Pass, et al – that some might expect this to be upon reading the synopsis. And in a way, it kind of is one of those films, albeit with more intellectual rigour and thematic heft. Old School with a philosophical bent.

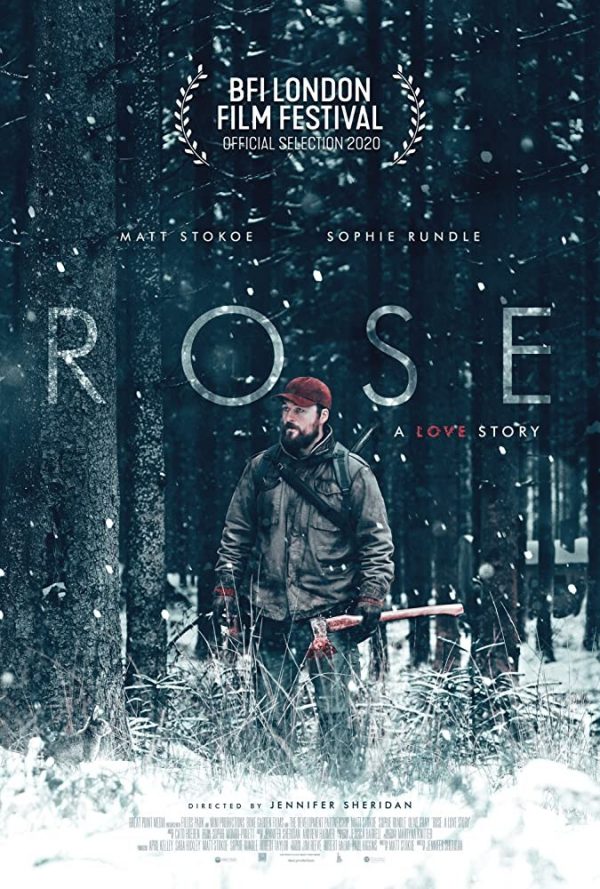

Rose: A Love Story (2020) dir. Jennifer Sheridan

This modern vampire story starts enigmatically and compellingly enough. A couple live out in the middle of the woods, where the mist rolls through the trees and there’s noone around for miles. Rose suffers from a strange affliction and her husband Sam tends to her every need. An altercation with a local chancer and the arrival of a mysterious stranger threaten to turn their quiet lives upside down.

Sheridan and her cinematographer Martyna Knitter shoot the surrounding wilderness beautifully and there’s a rich colour palette of deep reds and neon pinks inside the cottage. The problem with the film is the rather glacial pacing, there’s a lot of time spent on Rose and Sam’s daily routine – he goes out and sets traps, brings in dinner and has an hour or two of leech therapy whilst she sits at home, writes her novel and is crippled by self-doubt and image issues. She also eats a crimson coloured stew served up by her husband and has to wear a scented mask when around fresh meat. Rose is clearly a vampire, but the make-up and direction of the brief flashes of transformation have more in common with the modern zombie film.

The pace picks up again once Amber arrives seeking shelter, but ultimately the slow build up and enigmatic hints at what is literally staring you in the face have begun to grate long before we see Amber figure things out for herself. It’s disappointing because there are flashes of promise. The use of the vampire as a metaphor for caring for a loved one with a terminal illness is a great concept but it’s never really developed in an interesting way, preferring instead to fall back on well-worn cabin in the woods isolation and paranoia.

One Man and his Shoes (2020) dir. Yemi Bamiro

This zippy, lean documentary about the rise of the Air Jordan brand really takes off in the second half. The parallel rises in fortune of both Nike, Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls will be very familiar to anyone who watched The Last Dance during lockdown. What’s more interesting, is the way that One Man and his Shoes’ final half hour looks at how capitalism favours profit over human life and examines the positive and negative cultural impact of the Air Jordan brand.

It’s a balanced portrait of corporate America and of Michael Jordan himself. Neither hatchet job or hagiography, Bamiro and his contributors deal with the complexities of Jordan as a cultural icon – more forthright in his blackness than OJ Simpson but similarly quiet on the issues affecting African-Americans. Jordan’s telling silence is highlighted by the awkward clash between the aspirational way in which Air Jordans are marketed and their often disenfranchised customer base. As one speaker puts it, the trainers represent “wealth and status in areas where it is rare but coveted”.

This has led to multiple violent assaults and murders over these coveted trainers, the news footage and testimony by grieving family members being a shocking, eye-opening element of the film. One particular moment in which it’s revealed that Jordan sent a brand new, exclusive pair of Air Jordans to the grieving sister of a man killed for his shoes feels particularly insightful into how far removed Michael Jordan and the brand are from the lives and experiences of their customers. Perhaps it’s why Michael Jordan’s representatives deigned not to respond to interview requests. Regardless of the fact he doesn’t get a chance to have his say, Bemiro’s film never plays down the positives of Michael Jordan and the first black owned brand for corporate America, it just holds them both to a higher standard in the hope that they can and must do better.

Day 8 – October 12th

Ultraviolence (2020) dir. Ken Fero

“The UK is not innocent” was a familiar chant during the various Black Lives Matter protests across Britain this year and Ken Fero’s latest film outlines just how complicit we are, in unflinching detail. As a nation we’re just as guilty of blue on black violence as America, and the film highlights the deaths of Christopher Alder, Roger Sylvester, Paul Coker and Jean Charles De Menezes and their families subsequent fight for justice.

Ultraviolence is framed as a letter to Fero’s son, born during the aftermath of 9/11, a moment in our recent history in which, the filmmaker notes “violence was everywhere”. In his letter, he states that it’s up to future generations to take up the fight, tracing the outrage and horror at Vietnam to the “Stop the War” protests following Blair and Bush’s decision to invade Iraq and pondering how we’ve become so “contained” in recent years.

As Fero compiles this cinematic time capsule of the unrest of the mid to late 2000s, the film also becomes a comment on “the grand illusion of cinema” – how the moving image pushes the political agendas of the police and the military industrial complex. Fero seeks to liberate these images, to wrestle back some control of these stories from the hands of the UK media. The same media that spread untruths about the unarmed, innocent Jean Charles De Menezes to justify his being shot seven times in the head, the same media that highlight the fact Paul Coker had taken drugs so as to justify the need for fourteen police officers to (fatally) subdue him and bring him into custody.

The treatment of former soldier Christopher Alder, left to die face down on a custody suite floor whilst officers idly chatted and cracked jokes, poignantly links the treatment of our veterans with a history of racial prejudice and police brutality. None of these things exist in a vacuum and Fero deftly ties together the threads of Iraq, Islamophobia, institutionalised racism, a fatalistic populace, media bias and a broken judicial system to provide a searing indictment of the rot at the very core of the British ideal.

Day 7 – October 11th

One Night in Miami (2020) dir. Regina King

Imagining the conversations and arguments that may have taken place between Cassius Clay, Jim Brown, Sam Cooke and Malcolm X during a legendary night in Miami, Kemp Powers’ acclaimed play is adapted into a feature film for actor Regina King’s directorial debut.

Although it doesn’t quite transcend the theatrical origins of the original One Night in Miami is a compelling look at the state of the civil rights movement and the meaning of black power through the eyes of key figures from the worlds of sport, film, music and religion/politics. Whilst taking place on the night Clay became world champion and announced his intention to join the Muslim brotherhood, the core of the film is really the clash of personalities between Malcolm X and Sam Cooke.

Their scenes towards the end where they debate the political power of popular culture are absolutely electric and builds to one of the best uses of Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ in the Wind.

This is an impeccable ensemble cast – Hamilton’s Leslie Odom Jr captures the heart and soul of Cooke, Eli Goree nails the unique rhythm of Clay’s unique voice and Kinglsey Ben-Adir is a fully formed Malcolm X, feeling not just like a figurehead for a movement but as a fully formed, complex man. God only knows what awards season is going to look like next year, but One Night in Miami is a strong early contender.

The Intruder (2020) dir. Natalia Meta

Following a tragic event whilst on holiday with her boyfriend, voiceover artist and singer Ines experiences bad dreams, hears voices and, on returning to work, the microphones begin to pick up strange noises from within.

The opening scenes of the disastrous holiday delicately balance awkward comedy with domestic toxicity and an increasingly nightmarish atmosphere. The ending is charmingly off-kilter but feels like it’s from a film that is a lot less po-faced than the one that preceded it. There are occasional flashes of ghostly atmospheric horror, and the cinematography of the organ Ines and her choir rehearse in front of is terrific. However, it never adds up to anything as effectively creepy as it needs to.

There’s echoes of Peter Strickland, Brian DePalma and Dario Argento here in tone, subject matter and visual style. The problem is that the film never really finds a voice of it’s own.

Day 6 – October 10th

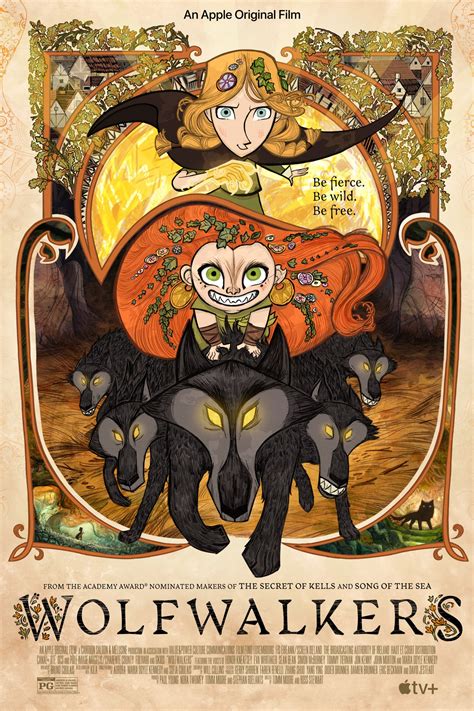

Wolfwalkers (2020) dirs. Tomm Moore, Ross Stewart

Werewolves have often been used as a metaphor for coming-of-age in genre cinema, and whilst Wolfwalkers is an enchanting fairytale rather than a John Landis movie, small elements of that tradition are evident here.

Irish based animation studio Cartoon Saloon’s latest film follows Robyn, a budding young wolf hunter who has her world-view changed by an encounter with the mysterious Mebh, a member of a mythical tribe of Wolfwalkers. The tribe live in the forest outside Kilkenny and are said to have the ability to turn into wolves. There’s a fun mismatched buddy comedy friendship between Robyn and Mebh which develops into a strong, sisterly bond. It’s this bond that will help them survive the deforestation and wolf cull ordered by the occupying English army, in which Robyn’s father serves.

Setting a kid’s film during the Cromwellian invasion of Ireland is a bold move, but unlike Disney’s Pocahontas, which mostly let the colonising forces off the hook, Wolfwalkers confronts these historic atrocities head on. Simon McBurney is terrifically odious as the Royal Protector whose blinkered religious superiority means misery and suffering for everyone around him.

For obvious reasons, the sectarian atrocities carried out during Cromwell’s invasion are dealt with through this battle for the forest and the Wolfwalker’s way of life. The result is a family film with sumptuous storybook visuals, real historical texture and a message of open-mindedness and acceptance that has never felt more relevant.

Wildfire (2020) dir. Cathy Brady

Forming an unexpected thematic double bill with Wolfwalkers is another tale of sisterhood and the damaging effects of the English occupation of Ireland.

Moving to the north, Cathy Brady’s debut feature juxtaposes the current post-Brexit uncertainty over the “Irish question” with the complex dynamic of two sisters who lost their parents in tragic, painful circumstances.

Returning after over a year of living rough, Kelly (a nuanced performance by the late Nika McGuigan) shows up on her sister Lauren’s (Nora-Jane Noone) doorstep. As the two sisters rebuild their fractious relationship and attempt to come to terms with the death of their mother, their actions increasingly put both sisters at odds with Lauren’s husband and their aunt. It’s these two characters which feel stultifyingly generic – the initially understanding but increasingly obstructive partner and overprotective stand-in matriarch are fairly well-worn kitchen sink tropes.

Perhaps it’s because McGuigan and Noone give such brilliant, one-of-a-kind performances that everyone else in the cast (including a few overly earnest extras) pale into comparison. The stand-out scene being an incredible pub dance sequence that boils over into an atmosphere of threat and historical recriminations.

It’s these two central performances that elevate the film above some occasionally predictable material and ensure that Wildfire is often a viscerally affecting look at mental health and traumas both personal and historical.

Day 5 – October 9th

Never Gonna Snow Again (2020) dirs. Małgorzata Szumowska and Michał Englert

This chilly, elusive satire of suburban angst starts strong – a mysterious stranger emerges from darkened woods with a massage table under his arm. Eventually arriving in a gated community somewhere in Poland, he sets about curing the residents of their various ills, both physical and spiritual.

This mysterious stranger is Zenia (played with an enigmatic charm by Alec Utgoff, best known to English speaking audiences as the slush puppy slurping Russian scientist in Stranger Things 3), a Ukrainian masseur who was born near Chernobyl seven years (to the day) after the disaster. Perhaps he’s radioactive?

As Zenia works his way through the various suburban households, the film shifts tones from arch satire, deep melancholy, atmospheric sci-fi horror and enigmatic eroticism, culminating in a magic show that is hilariously over-sexualised for an end of term school show. Incredibly striking visuals from cinematographer and co-director Michał Englert paper over the cracks in the more conspicuous tonal shifts whilst also adding to the sense that you’re not quite getting everything.

Is Zenia actually magical? Has being born in the shadow of a nuclear disaster embued him with magic hands and sexual superpowers, some sort of Uncanny Sex Man? Or is he simply providing some sort of placebo effect for these spoilt, disaffected suburbanites so that they can shift all their ennui and despair? I’m not sure. I’m not sure the filmmakers themselves know. Given how much fun I had trying to work it all out, I’m not sure it even matters.

Time (2020) dir. Garrett Bradley

Ava DuVernay’s eye-opening documentary 13th exposed how the American prison system was an extension of slavery and was rooted in continuing to keep the black man down. It’s a system that seems insurmountable without huge social changes, which under the current government don’t appear particularly forthcoming.

Garrett Bradley’s documentary Time portrays the personal cost of this system through the story of Fox and Rob Rich, a couple of “desperate people” who have done a desperate thing. The thing in question being the armed robbery of a Louisiana bank to help fund their ailing business. 18 years later and Fox has been released some years previously. She’s turned her life around to run a car dealership and gives talks on the broken system that has imprisoned her husband for 60 years without parole, whilst campaigning for his early release.

What is extraordinary is how Bradley conveys the weight and the length of this near two decade struggle in a lean 81 minute runtime. Time is an apt title, given how it captures so much of this lost time as a family.

A lot of this is achieved through the videos Fox recorded for Rob whilst he was inside, charting their (unborn at time of incarceration) children’s development into fine young men. It’s impossible to deny the power of seeing a mischievous young boy turn into a considered political science student in the literal blink of an eye.

The scenes where Fox is left on hold to the prison authorities are another sort of wasted time. At one point the person on the other end of the phone hasn’t even taken the time to chase up on Fox’s previous enquiry. At one point she exasperatedly exclaims to camera that the prison system don’t want to release Rob because “…they’ll all be trying to get resentenced.”

Fox and her family allow Bradley a great deal of access and intimacy as documentary subjects and it pays off in an ending that is almost overwhelming in its beauty and catharsis.

Supernova (2020) dir. Harry MacQueen

Bloody hell.

I’m sure there are some questioning whether or not Colin Firth and Stanley Tucci should be playing a gay couple but during the opening few minutes where they bicker over the relative merits of road atlas’ and sat-navs such concerns will be at the back of your mind.

Sam (Firth) and Tusker (Tucci) are embarking on a road trip through the North of England (beautifully shot by cinematographer Dick Pope). Musician Sam has a comeback recital scheduled and Tusker has planned for some old friends to surprise him en-route. The couple are also making their own plans to deal with Tusker’s deteriorating condition due to a recent dementia diagnosis.

The road trip, therefore, is a journey towards the inevitable. Mercifully, it goes for emotional subtlety over overwrought soul-bearing. Tucci’s portrayal of the ravages of the disease is a fine example of this. There’s no over-the-top, panicked loss of memory or zombified stupor. Instead there are far more nuanced physical touches – a struggle with a button here, an adjustment of the spectacles there. It’s a masterclass in conveying a world of suffering in just a look.

Aside from a slightly overlong sojourn into Peter’s Friends territory at Sam’s childhood home, this is an affecting two-hander about a couple reaching the end of their lives together. A startling revelation in the camper van threatens to tip the film into melodrama but MacQueen’s script and direction steadies the ship and gives us a meditative treatise on identity, love, life and death. By the end of the film, it’s actually the moments that we don’t see and the things that are left un-vocalised that affect us the most.

There’s no question that this is a tear-jerker, but it never feels manipulative or cloying. There’s a genuine warmth to Firth and Tucci as performers and something universal in the way the film deals with dementia and its effects on friends and family. I lost my grandmother to dementia earlier in the year, and so was clearly bringing a bit of my own baggage to this afternoon’s viewing. One moment in particular, involving Tusker’s handwriting really resonated with me, and it took a lot of strength to keep it together. Eventually though, as the credits rolled and my girlfriend entered the room to ask how the film was, I burst into floods of tears.

Like I say, bloody hell.

The Reason I Jump (2020) dir. Jerry Rothwell

Based on non-verbal autistic teenager Naoki Higashida’s bestselling book, Jerry Rothwell combines various passages with footage of other autistic teenagers from India, the UK, US and Siera Leone to provide a better means of understanding the world that they inhabit.

At times it succeeds through wonderful visual and aural poetry – for example, Broadstairs teen Joss’ obsession with green cable boxes writ large into this beautiful symphony in tandem with pylons in a field. However a lot of the time it relies on parents to bridge the gaps for audiences, talking about their parental experiences and how important Higashida’s book was to them.

As a result it feels less like the immersive portrait I was expecting and more of a traditional documentary held together by some strikingly beautiful imagery and some evocative sound design. Which isn’t to say that it’s a failure, it certainly forced me to interrogate my own experiences and ignorance around autism through presenting me with the multitude of complex layers to the condition.

That’s certainly the great success of both the book and the film in that it provides insight into this undiscovered country and opens up a conversation with those that we as a society have dismissed or ignored for so long. An occasionally beautiful paean to understanding.

Day 4 – October 8th

Undine (2020) dir. Christian Petzold

German director Christian Petzold excels at making familiar genre movies with a stripped back realist aesthetic. Look at his holocaust survivor revenge thriller Phoenix (2014) which never feels over-baked or exploitative. As much as 2018’s Transit is a treatise on our current refugee crisis, the setting feels like a dystopian future which is just around the corner.

With Undine he gives us a dreamy fairy tale romance, albeit one involving a historian specialising in city development and an industrial diver. We first meet Undine during a break-up with her boyfriend Johannes. “If you leave me” she warns him “you’ll have to die.” This doesn’t feel like the hysterical ravings of a woman scorned, it feels like a genuine threat. A threat rooted in mythology and a threat which Johannes ignores.

No matter, because after a meet-cute involving an exploding fish tank and a furious waiter, Undine falls head over heels in love with Christoph, an industrial diver. However, the couple soon find that the ancient myth of the water spirit is hard to escape.

Petzold’s urban fairytale is incredibly romantic, with previous Petzold collaborators Paula Beer and Franz Rogowski sharing easy chemistry with each other. The underwater scenes, meanwhile, have a real degree of elemental magic and mystery. Is that really Undine swimming with Gunther the giant catfish? Or is this a merging of Christoph’s romantic ideal of her and his own obsession with the local legend?

It might be a little too opaque for some tastes, but this modern mermaid story really worked it’s magic on me and is still swimming around in my head a day later.

200 Metres (2020) dir. Ameen Nayfeh

This Palestinian road movie follows Mustafa (Ali Sulimann) a desperate father who races to be by his son’s bedside following a road accident. Due to a mixture of historic oppression, the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and insufferable bureaucracy he has to take desperate measures to make it through the wall.

The first half of the film is strong on the dehumanising cattle herding that the Palestinians have to endure in their day to day lives. The claustrophobia of those cages and the uninterested Israeli border guards feels authentic and it’s hard not to empathise with Mustafa’s frustration as his valid travel permit is denied on account of an expired ID card.

It’s in the second half where the film starts to sag, there are certainly tensions along the way as Mustafa has to deal with shady people traffickers and a suspicious German filmmaker in order to be reunited with his family. And yet, there’s something artificial and all-too coincidental about the various obstacles he encounters in his journey.

And yet, aside from a roadside eruption towards the end, the effects of his circuitous route don’t seem to weigh particularly heavy on Mustafa’s shoulders by the end. Perhaps that’s a comment on the situation itself, that Palestinians have got so used to this imposition on their human rights and free travel that they stoically get on with it. However, I found the film’s climax lacking the dramatic heft or emotional release that it needed.

Chess of the Wind (1976) dir. Mohammad Reza Aslani

Screened just once and believed lost after the revolution, Iranian period piece Chess of the Wind was circulated amongst cinephiles on poor quality VHS until its rediscovery in an antique shop five years ago. It’s now been restored to its former glory by Cineteca di Bologna and the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project. And what an immaculate masterpiece it turns out to be.

Concerning a noble Iranian family’s dynastic struggle for their inheritance, it’s a rich, gothic tale of greed and entitlement. There are also hints of encroaching modernity in one brother’s desire to move into manufacturing and in the film’s closing pan over the city.

Comparisons have been made to Visconti for the portrayal of faded opulence and they’re warranted. One scene in particular finds the maid meticulously lighting a full chandelier for what, at first, appears like an unused room with everything under white sheets.

However, there’s also elements of Edgar Allen Poe as the shadow of murder and guilt lurk within the huge glass jars in the basement. The final sequence of the daughter’s desperate crawl into the basement bathhouse is pure Murnau, all coloured tints and horrified facial contortions.

This is a wonderful rediscovery, a sumptuous visual feast and disturbing gothic horror which should rightfully reassert it’s place in the canon of classic Iranian cinema.

Day 3 – October 7th

Mangrove (2020) dir. Steve McQueen

On the ceiling of the Old Bailey, there is a painting which is beset on either side by the words “Art” and “Truth.” Steve McQueen’s film about the trial of the Mangrove Nine expertly blends both.

Following repeated unwarranted police raids on his premises by the oily PC Pulley (punchably played by Sam Spurrell) and his cohorts, the Notting Hill community rallies to the support of restaurant owner Frank Crichlow (a masterful performance of barely concealed fury and frustration from Shaun Parkes). Taking to the streets to protest against the institutionalised racism within the Metropolitan Police, nine members of the group find themselves at the Old Bailey accused of “riot and affray”.

It’s beautifully shot – the mustard yellows, dark browns and bright greens of late 60s/early 70s decor have never looked so rich. McQueen crafts a compellingly told, tightly plotted film about events from our recent history which deserve much wider acknowledgement in both social and legal texts.

It’s also a great ensemble drama with a cast who, across the board, are at the very top of their game, ensuring that this is an impassioned tribute to the spirit of community and to those who stood up to a broken and prejudicial system.

Mangrove is a timely reminder that the UK is not innocent of the racism and prejudice that is often seen as a purely American problem and a stark statement of how far things have come and how far they still have to go.

Bloody Nose Empty Pockets (2020) dirs. Turner Ross, Bill Ross IV

“This town is losing it’s character” says the barman at the Roaring 20’s Cocktail Lounge, a Las Vegas dive bar which is imminently closing for good at the end of the night.

Pitching up at the bar to document the final night’s festivities, the Ross brothers’ film provides a booze sodden snapshot of a bar as a community space.

The first character we’re introduced to, head down on the bar, fast asleep is Michael who later opines that there is – “Nothing more boring than a guy who used to do stuff, who doesn’t do stuff any more, because he’s in a bar.” Stark comment on alcoholism though it is, I tend to disagree with Michael’s self-deprecatory observation. He’s a fascinating protagonist, a failed actor for whom the bar was a safe space and who appears to be harbouring some sort of unrequited desire for trans lounge act Rikki.

As other characters visit the bar for one final round, we get a glimpse into the rampant growth of Las Vegas, the way America leaves it’s veterans behind the minute their invalided out or their tour is over and the generational conflicts that eventually boil over into a petty, pathetic attempt to incite a bar brawl. All of this, whilst coverage of that fateful 2016 election plays in the background. It’s on these screens showing all-too appropriate news footage and clips from old films where there are hints as to where the authenticity ends and staged improvisational drama begins.

You see, the Ross’ have carefully selected their barflies and whilst that has riled some purists, for me it hardly matters. Here in 2020, the lines between truth and fiction have never seem more blurred and through this evocative portrait of an American bar, we find the state of America itself. The only downside of the more artificial elements is that it means I can’t, in all good conscience, sum this film up as “an episode of It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia directed by Frederick Wiseman.”

Shirley (2020) dir. Josephine Decker

Biopics are often quite rigid affairs as the documented events of a subject’s life often prove to be creatively stultifying. Shirley avoids this problem by providing a fictional account of the writing of Shirley Jackson’s second novel Hangsaman and in doing so becomes more of a psychological horror than a literary biopic.

At the centre of the film is an extraordinary performance by Elisabeth Moss as Shirley. The way she seamlessly shifts from alcoholic stupor to genius writer to anxious agoraphobic to bitter, spiteful employer and eventual seductress is a joy to watch. It’s hardly surprising that young, accommodating professor’s wife Rose (a chameleonic Odessa Young) is drawn into her orbit.

The two form a strange bond, as the young woman and local missing person’s case inspires Shirley to start writing again. She also provides the audience an insight into the relationship between Shirley and her husband Stanley (a pompous, lecherous Michael Stuhlbarg) as they each mould the young couple into ciphers for their own complex marriage.

I don’t think the film drills down into the wider themes of small-town gossip and sexual inequality in as satisfying a way as you would hope but three gifted performers, a claustrophobic atmosphere and some dazzling visuals ensure it’s a hugely engaging watch. Terrifically competent, and unlike Stanley, I don’t mean that as an insult.

Day 2 – October 5th

Stray (2020) dir. Elizabeth Lo

In Istanbul, it is illegal to euthanise or confine stray dogs. Documentarian Elizabeth Lo follows a few of these strays through the streets of the Turkish capital to provide a unique perspective on marginalised lives. Thankfully, Lo never overplays her hand in drawing comparisons between the homeless young Syrian migrants and their canine counterparts.

Depending on your tolerance for observational documentary making you may find yourself craving some weightier commentary. Especially as the dogs weave their way through mass protests and brightly lit shopping arcades whilst various broadcasts about Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan play in the background.

Once you get the point, the pace can become rather meandering in lieu of a more pronounced thematic heft. A Go-Pro puppy heist adds a temporary frenetic energy to the film but it’s a jarring change in style that threatens to undermine the gentle padding through the streets and ports, observing how canine and human life co-exists on the city’s margins with melancholic, often drily funny results.

Shadow Country (2020) dir. Bohdana Slámy

This harrowing historical drama tells the story of how a small town on the Czech-Austrian border was buffeted by historic border conflicts, Hitler’s annexation of Austria, the holocaust, the Second World War and the revenge taken against the Sudeten Germans.

As a story of sweeping historical change told through a small village it calls to mind Edgar Reitz’s Heimat and the rich black and white cinematography furthers the case for comparison. That being said, the village feels less authentic and many of the inhabitants aren’t nearly as fully-formed as the residents of Schabbach.

Which isn’t to say that the film’s brutal second half lacks the required impact. Csongor Kassai is extraordinary as the tortured former resistance fighter sent back to town to deal with his “German” neighbours. What follows is a treatise on how a thirst for revenge and xenophobic tensions boil over into cycles of appalling violence. It’s gruelling, yet incisively relevant for our current moment.

Herself (2020) dir. Phyllida Lloyd

Pleasantly surprised by this, I rather sniffily dismissed it as a quirky Britcom from the director of Mamma Mia! but this Irish drama about literally rebuilding your life following years of domestic abuse has a harder edge than I was expecting.

Having left her abusive partner after a brutal assault which has left her with nerve damage, Sandra (played by co-writer Clare Dunn) is trying to find a permanent home for herself and her two daughters. Stuck in a housing system that hinders rather than homes people, she chances upon a YouTube video about how to build your own house. With the aid of family friends and the kindness of strangers Sandra sets about rebuilding her life.

Ultimately, this is an uplifting film with humour, quirk and the obligatory house building montages set to upbeat pop music. However, there’s also a rich vein of the Loachian tradition running through it. Whilst it’s more The Angel’s Share than I, Daniel Blake the film makes some strong points about the flaws in the housing system and how poorly the authorities treat victims of domestic violence. It’s a real crowd-pleaser with a 2020 appropriate paean to kindness and a gentle plea for urgent changes to our social welfare systems.

Siberia (2020) dir. Abel Ferrara

Willem Dafoe and Abel Ferrara team up for a sixth time, and I can’t help but wish they hadn’t bothered.

Dafoe is a barman in the remote Canadian wilderness who has to deal with random bear attacks, a grandmother who pimps out her pregnant granddaughter and something truly disturbing in the cellar. That’s not actually the plot, because there isn’t one. Siberia is an attempt to explore dreams and the human subconscious through cinema.

There is certainly a dreamlike atmosphere conjured up by disjointed scene transitions and some jarring juxtapositions, occasionally lapsing into upsetting, nightmarish imagery. The visuals aren’t the problem here, the location work is absolutely stunning and it’s impossible to dislike the image of Willem Dafoe dancing round a maypole with a group of children, grinning maniacally in a sun dappled meadow.

Instead, it’s the pompous, wanky dialogue between Dafoe and himself (also playing his father), a magician, a mystery man in a cellar and a woman who is either an ex-lover or his mother. So far, so Sigmund.

It’s these heavy layers of pretension and cod-psychology that makes the experience of watching Siberia a bit like wading through fifteen feet of snow.

Day 1 – October 2nd

Mogul Mowgli (2020) dir. Bassam Tariq

The film finds Zed, a British-Pakistani rapper who’s struck down by a debilitating disease just as he’s about to hit the big time. Forced to spend more time with his parents as he embarks on the road to recovery, he’s haunted by generational trauma and his own insecurities about his career.

Whilst Riz Ahmed (who also co-wrote the film) delivers a powerful portrayal of masculinity in crisis, the film itself occasionally veers into movie of the week territory in the hospital scenes. It’s disappointing because this has a lot more going for it than being a simple “recovery from illness” movie. It’s also a film about the British Asian experience, cultural erasure, rap as a means of expression, the post-colonial trauma of the Partition and it’s damaging legacy. Unfortunately none of these elements knit together in a satisfying way and instead we have to make do with a heavy handed metaphor – Zed’s body is literally at war with itself.

The Painter and the Thief (2020) dir. Benjamin Ree

An oftentimes moving documentary about the friendship between an artist and one of the thieves who stole two of her paintings from an Oslo gallery. As the friendship between painter Barbora Kysilkova and Karl Bertil-Nordland develops, they develop a strong bond and share the various traumas each of them have endured in their lives. There’s an interesting moment two thirds of the way through the film where Karl notes that he’s never told Barbora about the good times in his life, perhaps because as an artist she’s drawn to the darkness.

The most powerful moment is when Karl sees Barbora’s portrait of him for the first time and breaks down in tears, becoming almost hysterical. It’s a profoundly moving moment in a film that’s all about the power of artistic representation and of being seen. This is slightly undercut by Barbora’s need to find out what happened to her paintings, which leads to a slightly underbaked mystery narrative that feels as if it’s been bolted on to appeal to the mainstream true crime audience.

The Disciple (2020) dir. Chaitanya Tamhane

Highlight of the day was this fascinating drama about the quest for musical excellence within classical Hindustani music. Sharad is a dedicated singer of Khayal and the classical raag. He waits on his teacher hand and foot, and spends his free time listening to lectures by the enigmatic musical guru Maai in the pursuit of musical excellence.

If that sounds impenetrable then don’t worry, the themes at the heart of The Disciple are quite universal. What do we sacrifice in pursuit of our careers? How do we balance the fine line between art and commerce? Who decides what’s art and what’s populist trash? And what happens when it turns out that we’ve not quite got the skill to go all the way in our chosen field?

Sharad is a fascinating protagonist, a deferential pupil, a tortured artist and, frankly, a bit of a hipster snob. It’s due to musician Aditya Modak’s textured performance that we feel as much sympathy for him as we do frustration and disgust at his bitter and petty lashing out at younger artists striking out ahead of him. Some have pointed to the similarities with Whiplash, which is a fair comparison. However where that film felt full of caricature and light on nuance, Sharad’s pursuit of musical excellence at the cost of everything else feels much more complex and much more real. Or maybe I’m a bit of a hipster snob too.